The analysis of the recent history of Afghanistan cannot ignore the, albeit synthetic, illustration of key aspects of Afghan society. We summarize them by grouping them into three main areas: geographical location, ethnic and tribal fragmentation, interpretation of Islam and sharia.

Geographical location. Without going back to the most ancient events, the geopolitical role of the area has determined the history of the last two centuries: “buffer state” between the Russian Empire and the British Empire in the nineteenth century; last battlefield, in the 80s of the 20th century, between the USSR, close to collapse, and the United States, intent on guaranteeing their role as supporters of the world order; route of the planned oil pipeline that would have allowed the transit of Central Asian hydrocarbons towards the Arabian Sea, avoiding Iran.

Ethnic fragmentation and tribal society. It is estimated that there are over 50 ethnic groups present in Afghanistan (see figure) and that 30 languages are spoken there, of which the most widespread are Pashto and Dari. Ethnic and religious affiliation are intertwined (Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks and Turkmens are Sunni, the Hazara minority is Shiite), characterizing power relations consolidated over time: the Pashtuns, since the 18th century, have provided the country’s ruling class sharing power with the Tajiks, the second ethnic group, while the Hazaras have always been victims of discrimination. The main ethnic groups have their own “moral code” (Pashtunwali for the Pashtun ethnic group) whose basic elements are very similar: hospitality, revenge, autonomy and honor. Ethnicities intersect, for most ethnic groups, with a tribe-based society. As Elisa Giunchi illustrates well in her book on Afghanistan, ethnic groups and tribes are, however, “fluid” concepts: “The tribe, like ethnicity, is not a closed and internally homogeneous group: it is composed of concentric circles of solidarity of clannish, familial and geographical which continually, depending on the circumstances, create and break down alliances. The primary solidarity group (qaum) is, therefore, situational and relative. The result is an extremely unstable picture…” and with which the central power must necessarily measure itself.

Interpretation of Islam and sharia. In such a fragmented reality, Islam is the only common reference for all Afghans. Until the 1990s, Afghan Islam was strongly influenced by Sufism, recognizing itself in a mystical dimension of Islam, so much so that Afghanistan was considered the homeland of Sufi saints. Sufism has shaped Afghan society and politics for much of the country’s history, but the first Taliban government (1996-2001) prohibited all its practices and since then the dominant one has been a fundamentalist interpretation of Islam and especially of sharia , the code “imposed by God”.

Women in traditional Afghan society

It is essential to understand the condition of women in Afghanistan to understand the theme of the “moral code” that connects the various ethnic groups and tribes. We quote Giunchi again: “Throughout the country, beyond ethnic heterogeneity and regional particularisms, honor defines the prestige of the qaum and its members. Honor resides in the ability to protect property on zan, zar and zamin (respectively: women, gold, land) and is linked in a particular way to female behavior: the honor of qaum depends not only on the chastity of unmarried women and on fidelity of married women, but by the modesty of their behavior and their obedience to fathers and husbands. Every form of deviance can become a violation of honor, which reflects on the entire group to which one belongs.”

A code compliant with sharia (in some respects even more restrictive), the application of which has therefore found consensus and fertile ground. Well before the Taliban imposed it, tradition, especially in rural areas, subjected Afghan women to heavy restrictions: “Women are exchanged to resolve disputes between groups; they are rarely sent to school, enjoy little freedom of movement and therefore have limited access to health facilities; they are subjected to the will of their father and, after marriage, to that of their husband…”.

The slow process of modernization

For a precise description of the facts, please refer to the reading of the Chronology, here we will try to highlight the salient features of each period and the impact that these had in the lives of Afghan women.

After the partial victory of the Afghans in the third conflict with the British Empire and the recognition of full independence in 1921, King Amanullah, with the support of both the nationalist urban elite and the more conservative areas, began a period of reforms. In 1923 a Constitution was promulgated that recognized the equality of all citizens before the law; we try to discourage the use of the veil and the segregation imposed on women; female education is encouraged; a family code is promulgated that prohibits early marriage and places a limit on marriage expenses; an attempt was made to implement an administrative reform that assigned government offices the task of settling some disputes relating to the family sphere, which until then had been the prerogative of tribal chiefs.

Amanullah’s reforms, which are accompanied by the reorganization of the tax system to finance the new structure of the country, provoke the reaction of a society anchored to tradition. The king was deposed, but Zahir Shah’s rise to power in 1933 marked the resumption of the process of gradual modernisation. With the appointment of Mohammed Daud as prime minister, the reforms extend to the legal status of women, however provoking a reaction from rural environments. In 1964 a new Constitution was promulgated which legalized political parties, recognized freedom of the press and established the priority of laws enacted by Parliament over sharia, although it established that “state legislation could not violate the fundamental principles of Islam”.

On the international front, despite the sovereign having a pro-English policy, in the 1950s there was a rapprochement with the USSR, substantially motivated by the dispute concerning the Pashtun territories located in Pakistan, east of the Durand Line (the controversial border established in 1893 between Afghanistan and British Empire, not recognized by the Afghans after the creation of Pakistan in 1947).

The openings of Zahir Shah and Daud lead to an intellectual effervescence in the cities with the birth, on the one hand, of communist movements pushing for an acceleration of change and, on the other, of Islamist groups opposed to the modernization process and intending to replace the monarchy with an Islamic state based on sharia. In 1965 the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) was founded while some of the main protagonists of the political and military scene of the following years were formed in fundamentalist university circles. In the same year the Communist Youth Organization (OGP) was born, which differs from the PDPA due to its pro-Maoist position (let’s not forget that, in the communist galaxy, these were the years of strong opposition between pro-Soviet parties and pro-Maoist movements) . The Shulai movement, the name by which the Maoists are known in Afghanistan, remained clandestine and promoted the student, peasant and worker revolts that characterized the Afghan 1968 movement.

A lost bet

At the beginning of the 1970s, Afghanistan was constantly balanced between progressive pressures and revolts, fomented by the mullahs, against any reform. At the same time, the country’s economic conditions are not improving and, also due to a prolonged period of drought, poverty is spreading, further fueling the protests. The 1973 coup replaces the constitutional monarchy with the presidential republic led by Daud. Following a wave of arrests, the leaders of the Islamist groups (including Hekmatyar, Rabbani and Massud) took refuge in Peshawar where they obtained the support of the Pakistani government, local Islamism and the secret services.

While in the international field the rapprochement with the USSR accelerated, within the country those previously acquired freedoms were restricted and in 1977 a new Constitution was issued which defined the new presidential republic based on a unicameral parliament and a single party. 1977 is also the year in which the activist Meena Keshwar Kamal founded RAWA (Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan) with the mission of fighting for equality and social justice for women, for fundamental rights to education, to legal defense, medical care and for liberation from poverty and violence.

The following year, the coup d’état at the hands of the PDPA (the so-called Saur Revolution, i.e. April Revolution) overthrew Daud, bringing Taraki and then Amin to power. The new government is characterized by a very harsh repression of political opponents (thousands of members of the Shulai movement are arrested or killed) and by an acceleration of those reforms that were to have such a profound impact on the Afghan tradition, however, imposed in an authoritarian way and without considering the delicate balance of rural society. The result is an opposition that takes various forms: against authoritarian and repressive policies; against the dismantling of a life marked by tradition and Islam; against an almost entirely Pashtun government by the Hazara and Tajik minorities; of Islamist groups fomented by Pakistan.

Meanwhile, the USA, which with the Khomeinist revolution of February 1979 in Iran had been left orphaned of its strategic ally in the area, sees in the Afghan chaos the opening of a new opportunity: “Give the USSR its Vietnam war”, as the former US national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski would declare twenty years later, revealing that the CIA had been authorized by President Carter to send aid to opponents of the Kabul regime as early as July 1979; Brzezinski admits that the Administration had “consciously increased the likelihood” that the Soviets would intervene militarily.

Three quarters of the country are involved in riots. Amin asks for Soviet protection and in December 1979 USSR troops enter Afghanistan.

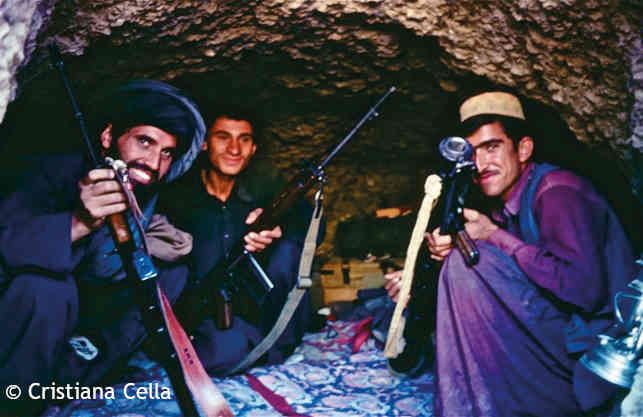

The Soviet invasion and the consolidation of Islamic fundamentalists

While massive anti-Soviet student demonstrations take place in Kabul, in Peshawar, Pakistan, the armed resistance against the Soviets is organized into Islamist groups (mujahideen) characterized by a single, common vision of society based on the moral code described above and on sharia as a legal system of reference. But the Soviet invaders were not the only ones fighting, weapons in hand: various progressive formations, unfortunately fragmented and lacking a unified leadership, opposed the Soviets and the fundamentalist groups, aware that a future government of the Islamist mujahideen would be catastrophic for the village. The two-front war that these groups had to fight decimated them, recording thousands of deaths. However, the survivors were able to keep their democratic and secular battles alive in the years to come.

However, it will be the Islamist groups that will have the economic, military and strategic support of: the USA, in an anti-Soviet key; Saudi Arabia, to strengthen its Islamic credentials (especially with an anti-Iran function); Pakistan, to stifle Pashtun claims on Pakistani territory. According to journalist Ahmed Rashid, adding the contributions received from their three main supporters and other sources, in the 1980s the mujahideen received more than 10 billion dollars: “Before the war the Islamists enjoyed weak support in Afghan society but, with the money and weapons received from the CIA and with the support of Pakistan, they had managed to broaden their base and exercise a very strong influence”.

Then there is another element that strengthens these groups, and which will have a devastating impact on the future of Afghanistan: during the years of war, thousands of volunteers from 40 different countries converged on refugee camps in Pakistan to go and fight in Afghanistan. With consequences that are not limited to the area: it is al-Qaeda’s number two himself, Ayman al-Zawahiri, who claims that in those years Afghanistan represented the incubator of the jihadist movement.

In the meantime, during the years of occupation, RAWA continued its work of raising awareness and supporting the population, but starting from March 1982 the founder Meena, who was assassinated in 1987, and the management of the organization moved to Pakistan where, in the refugees from Quetta, founded the Watan schools for the children and women of the camps, offering them both a refuge and educational and professional training courses.

The warlords and the appearance of the Taliban

After 9 years of war, with estimates of civilians killed ranging from 600 thousand to 2 million, over 7 million refugees between Pakistan, Iran and internally, in February 1989 the Soviet troops withdrew from Afghanistan, leaving the puppet regime of Najibullah against whom the mujahideen continued to fight until the complete conquest of the country in 1992.

Upon the deposition of Najibullah, the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan is proclaimed; the new government, led by Rabbani, with Massud as Minister of Defense and Sayyaf of the Interior, immediately issued a series of decrees to impose an obscurantist vision of society, forcing, for example, women to wear the burqa.

The country is devastated and far from pacified: between 1992 and 1996 the various Islamist groups compete for power in the various areas of the country and the already fleeting ideological differences give way to the particularistic interests of the various groups, with an alternation of alliances, betrayals, changes of position that are difficult to follow. Dostum, Massud, Hekmatyar, Sayyaf, Rabbani, Ismail Khan are the “warlords” who, in the indifference of the international community, clash over the heads of the Afghan people, committing crimes against civilians, all without distinction. In addition to the horrors of armed clashes and bombings, the Afghan population is subjected to abuses of all kinds, with checkpoints that paralyze all types of trade and the imposition of “duties” and taxes that starve a population already reduced to extremes.

And it is precisely in this context that the Taliban make their appearance. The “students” trained in the madrasas of Peshawar set themselves up as champions of “legality” and precisely because they promise to put an end to the oppression of the “war lords” they initially find the consensus of the population, in particular in the Kandahar area where the situation is particularly degraded. But above all, the appearance of the Taliban is supported by Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, concerned about the ungovernability of the country and, once Kabul was conquered and the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan was founded in 1996, it is also seen favorably by the USA: from on the one hand the Taliban are going to counter the influence that Iran has on some Islamist groups (Hekmatyar), on the other a stabilization could allow for the construction of that oil pipeline which is so important for the Americans for the purposes of exploiting the deposits of the Caspian Sea ( let’s not forget that these were the years of post-Soviet chaos and therefore its dismantling has whetted various appetites).

1996-2001: the years of Taliban terror

Ban on the consumption of pork and alcohol, obligation for men to grow beards, establishment of a police force “for the diffusion of virtue and the prevention of vice”, death penalty for adultery by flogging for men and stoning for women, cutting off of hands and in some cases even of a foot for common criminals, ban on all creative activities (television, music, cinema, theatres, video games, chess, kites), strict application of sharia and Pashtunwali in the whole country. This is the life imposed by the Taliban on Afghans, but those who pay the greatest price are, once again, women: in addition to the obligation to wear a burqa, there is also a ban on traveling without being accompanied, the suspension of all forms of education and the expulsion from schools and universities, the ban on working, no type of protection against domestic violence which, on the contrary, is justified, the ban on being examined by a male doctor, which means a ban on treatment.

During the years of the Taliban regime, Afghanistan also became the world’s leading producer of opium: it is estimated that in 2000, 75% of the world’s opium production occurred in Afghanistan. The Taliban control 96% of the poppy fields and make opium taxation their main source of revenue. Meanwhile, the mujahideen factions that had torn the country apart fighting among themselves reunite in the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan, known in the West as the Northern Alliance, continuing to fight the Taliban. With the fall of Mazar-i Shariff in 1998, all major cities and roads are under the control of the Taliban, while the Northern Alliance controls only a limited portion of territory in the north-east of the country.

Finally, Afghanistan becomes the safe haven of Islamist terrorist groups, first and foremost al Qaeda.

American wrath and “pax”.

September 11, 2001. Suicide attacks in the USA organized by al Qaeda cause 2,977 deaths and over 6,000 injuries. The American president orders the Taliban government to collaborate in the persecution of those responsible and, once the unheeded ultimatum expired, on 7 October he launches the military operation Enduring Freedom with intense bombings on the country in support of the anti-Taliban resistance of the Northern Alliance. In the space of just over a month the Taliban were forced to leave the main cities and take refuge in the mountains.

Since the beginning of the US operations, various organizations have opposed the invasion: some, still linked to the Maoist movement, operate clandestinely, but in 2003 (in view of the 2004 presidential elections) the Hambastagi party was born, of secular and democratic inspiration which fights against every form of Islamic fundamentalism, against foreign occupation and for a secular democracy that guarantees rights to all, especially women.

In 2006, control of operations in Afghanistan passed to NATO with the ISAF mission until 2014 and then, until July 2021, with the Resolute Support mission.

Remembering to refer to the box for the detailed chronology, here we summarize the characteristics of the 20 years preceding the “return” of the Taliban, focusing on the 4 protagonists: the Kabul government, NATO, the Taliban and the Afghan people.

The Kabul government

Over the past 20 years, Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani have succeeded each other at the helm of the country with Parliamentary and presidential elections are always subject to strong disputes. But regardless of who sits in the president’s chair, Afghan governments are characterized by:

- very high levels of corruption: since 2002, cascades of dollars have rained down on Afghanistan destined to equip the Afghan army, build the infrastructure and support the development of a very poor country, but what reaches the Afghan people are only a few drops and the most of this money ends up in the hands of those sitting in the various centers of power;

- majority presence of fundamentalists: since the first elections in 2005, the leaders of the fundamentalist groups have sat in parliament and, in the following years, following the “national plan for the reconciliation and reintegration of the moderate Taliban” promoted by Karzai, exponents of the past Taliban regime they enter the government structure in various capacities;

- lack of control of the country: the central government effectively controls only Kabul and some large cities while the rest of the country is in the hands of local warlords and the Taliban.

NATO

The substantial failure of the NATO intervention can be traced back to multiple factors: lack of pacification of the country and high number of civilian deaths; lack of knowledge of the relational dynamics of Afghan society with consequent conferring of power on intermediaries who have robbed the population of aid intended for development projects; inadequate training of the Afghan security forces, in addition to the overestimation of their number (the 350 thousand soldiers of the Afghan army were probably less than half: the numbers were partly inflated by the national government and partly by the local army commanders, who in this way they could pocket the salaries of the soldiers they had abandoned or deserted).

The Taliban

The Taliban have never disappeared from the political scene of Afghanistan and since 2009/2010 they have progressively managed to control ever larger parts of the country, enjoying the support, albeit unofficial, of Pakistan, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Opium trafficking has represented, and continues to represent, an important source of financing.

The Afghan people

If the humanitarian interventions that arrived in the country after the fall of the Taliban in 2001 have partly alleviated the condition of extreme poverty in which the Afghan people found themselves, the result is not commensurate with the extent of the effort. As we have seen in the various in-depth studies, in 20 years it has not been possible to build an alternative economy to the one substantially based on the cultivation of poppies and the processing of opium. Finally, the much vaunted achievements on the topic of freedom for women: if it is true that in these 20 years the worlds of education and work have opened up for some women, it is also true that this has happened almost exclusively in the cities, leaving the rural areas at the mercy of traditional oppressive and oppressive relations.

The “return” of the Taliban

In light of what has just been written, talking about the “return” of the Taliban to describe what happened in 2021 is decidedly inappropriate.

The acceleration of the process that will lead to the capitulation on 15 August 2021 takes place starting from 29 February 2020 when, after two years of more or less secret agreements between US emissaries and the Taliban, the Doha Agreement is signed which formally ends the conflict between the USA and the Taliban and provides for the total withdrawal of the US armed forces from Afghanistan by 31 August 2021. The Taliban offensive begins in May 2021 which, within four months, will lead to the conquest of the entire country. And while the Afghan security forces dissolve like snow in the sun, Ashraf Ghani hastily flees and the last American soldiers board the planes that will take them back to their homeland, the epilogue of 20 years of NATO occupation takes place in Kabul airport with the tragic scenes we all remember.

As soon as they settled in Kabul, the Taliban proclaimed the “second edition” of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.